My grandfather, Joseph Simon, started S & S Key Service on the South Side of Chicago in 1887. My father, Harry Simon, began working at S & S around 1910 and took over ownership from his father in 1917.

From the start, S & S Key would open for business at 7:30 a.m. and close somewhere around 6:30 p.m., six days a week. Service was offered 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and everyone rotated for night service. First thing every morning, the store was completely cleaned to ensure that everyone who walked in found a spotless store. Every day, the service personnel wore clean uniforms with matching pants and shirts embroidered with the company name.

Non-emergency calls were scheduled by appointment for the outside people. These included auxiliary lock installations, door closers and apartment house mailbox servicing. My father bought the uniforms. He also furnished the automobiles, purchasing them based on the size of the trunk.

Lock service vehicles had three tool kits: one for combination changes, one for mortise locks that contained various “popular” parts and one for auxiliary lock installations. To service door closers, we kept a small inventory of rebuilt closers in the service vehicles. Inventoried units were exchanged for the one on the door. Billing for the repair job was done after we knew what was involved in rebuilding the closer.

Apartment vertical mailboxes installed in the walls of the vestibule required an estimate first. Then, if the lock couldn’t be repaired in the wall, the Post Office was called out to remove their lock so the mailbox could be brought back to the shop. In the shop, doors and compartments were straightened out; new locks were installed and the face was refinished to look like new. After our work was completed, Post Office workers met our people on the job and reinstalled their lock. Mail would not be delivered until the mailbox was secured.

Owners of apartment buildings wanted their lobbies to look appealing to tenants, visitors and their prospective clients. To add to the luster of the mailboxes, we introduced universal name cards that went into the name slots. They were heat-embossed onto black plastic with white or gold letters. That idea was so successful that real estate firms from all over the city mailed us their list of tenants’ names to fabricate name cards. Based on a yearly contract, every time a new tenant moved in, name cards were provided. That service led to new lock and door closer work from real estate companies and property management companies.

Around 8 a.m., the customers started to come in. They brought in their locks, doors with locks attached, and even car doors with the locks in them because they didn’t know how to remove them. Whole automobiles were directed to the back of the building for service as it was dangerous to work in front on the street. Keys had to be fitted, main door lock springs replaced and cylinders rebuilt or recombinated. Paving was expensive, and I often saw a load of cinders from the coal-burning furnaces in neighborhood buildings being dumped and spread out in the service area to avoid walking in dirt or mud. Sun, rain, snow or freezing weather -- all the work was performed on cars outside. There were times that the shop got so busy that a “please take a number” policy was issued to service customers in the order that they arrived.

Key cutting was a major source of income. Often, four to five locksmiths worked the front counter running three Keil automatics and other machines just to keep up with the customer traffic. Claim checks for repair work were often given. When picked up, locks were always cleaned and the exposed brass or bronze parts re-polished.

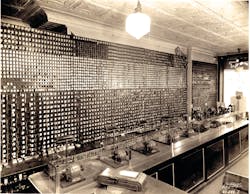

Unlike today where only a few popular key blanks are needed, locks from all manufacturers such as Barrows, Clinton, Earle, Penn, Reading and Sager -- a few names from the past -- each required a specific key blank. An 8’ high by 24’ long keyboard was hand-built. I remember my brother Gene and I screwing four-inch “L” hooks into the boards. Cylinder, bit, flat, barrel, railroad bronze, and other types of keys were grouped together. The upper section of the key board was devoted to precut original trunk, foot locker, bit & barrel keys that were identified by the number on the lock. Specialty keys like foreign lock keys were slower movers and were kept in the upper section. In a short time we found the main board wasn't enough. A second board placed in the very front of the store on the wall measured 6’ by 6’. This board was devoted to automobile keys from late models and cars long gone, such as Maxwells, Cords, Duesenbergs, Essex, Franklins and others that car buffs would recognize.

The company flourished based on the cleanliness of the store, the professionalism of the servicemen and the fact that we could make almost any key and make it right for all locks. “Keys made while you hesitate” was our slogan.

Two Keil automatics, serial numbers 2 & 3, were in constant use. Francis Keil, owner of Keil Lock Company, gave them to my father as a thank you for assisting him in the invention of the automatic machine (and they were still in daily operation years later when Gene and I sold the business to several of the locksmiths who worked for us).

Key machines were devoted to specific locks. Keil’s 6 ½ and 4 ½ turrets and Ilco’s Simplex and Duplex were used for key duplication. We also had a pair of Segal’s manual machines. There were two machines to make tubular keys and three to make Bell and Mill’s keys, the forerunner of today's sidewinders. My father built machines for making tubular keys directly from the tubular cylinder and sidewinder type. He also made an automatic code machine to make sidewinder type keys. Ilco code machines were set up just to make Ford, Chrysler or General Motors and other autos. We had a code machine just for mailbox locks, and one for locker locks. And of course, we had code machines to make standard pin tumbler keys from code.

Our customer base was the City of Chicago, and customers came by car, streetcar and elevated trains just to have their keys made. We maintained a selection of the best locks that were available. It would be hard to remember how many times a customer wanted the same auxiliary lock that we had on our front door. If we trusted it, they knew it had to be good. That lock was a solid bronze Keil rotary bolt deadlock. We took it off the door it and placed it directly into our customers’ hands every time. Then, after they left, we replaced it with another rotary bolt lock. The screw holes wore out in the wood door from the removing and reinstalling the lock. Often the screw holes had to be plugged in order for the mounting screws to stay in place.

TITLES and DEGREES

Two titles were applied in those years, locksmiths and master locksmiths. Locksmiths worked for a builder’s hardware company, a hardware store or a farmers feed and supply operation. Their work consisted of a key to be made, a cylinder to be recombinated and/or minor repairing of mortise, rim, and padlocks. Most of the mortise and rim lock work consisted only of the replacement of broken springs. That wasn’t their only job.

Master Locksmiths owned and operated their own establishments. They serviced residences and commercial and institutional facilities. They repaired, rekeyed, and serviced automotive locks. Since the number of lock functions was limited, Master Locksmiths would design and build locks for a customer’s specific needs. Many Master Locksmiths also serviced safes, vaults and safe deposit boxes. Safe work, in addition to locksmithing, offered customers a total package. Master Locksmiths taught and shared their knowledge with their children, resulting in 2nd, 3rd and 4th generation locksmiths. In many instances, apprentices were taught only what they needed to know. If an apprentice stayed with a company long enough, he would eventually learn the trade.

The Master Locksmith could not always depend 100 percent on lock work to make a living. Door and floor closer repairing was a must. Apartment house mailboxes had to be service and maintained. They also did bicycle repair, tinsmithing, and sharpened scissors, lawnmower blades, etc. Many locksmiths also maintained a small hardware store with products that were related to locks.

Service work consisted of fitting keys and keying cylinders. Lock types included bit key, lever tumbler, mortise and rim cylinders. In Chicago 1939, 99 percent of the locks were mortise or rim and there was no industry standardization like we have today. Mortise locks came in just about all sizes, shapes, and backsets. Mortise lock cases were cast iron that had to be welded or replaced, and parts were cast brass and hand finished. Interchangeable parts were not a well-known commodity. When hubs wore out, they had to be rebuilt with a welding torch to add back material or machine one from scratch. Replacement of knob spindles was a big business – one of the few replacement items that were available to the trade along with cylinder set screws, etc. During this time, the key-in-knob lock was in its infancy, with only a few lock manufacturers offering them.

Master Locksmiths were always called for lockouts. Auto lock servicing was usually a significant portion of their business, as automotive locks were usually not cared for, and weather conditions would cause constant failure. Not only did the cylinders have to be serviced, but also the main door locks were a constant source of repair due to all the various springs that supported the outside and inside handles.

TOOLS AND EQUIPMENT

Standard tools, such as hammers, screwdrivers, and pliers were available. However, the Master Locksmith had to hand-make his specialty tools like picks, shims, cylinder disassembly tools, car-opening tools and safe servicing tools. A limited selection of key duplicating equipment was on the market from Keil Lock Company and ILCO (Independent Lock Company). Most of the major lock manufacturers offered a simple basic key cutting machine for their pin tumbler locks. Some locksmith distributors offered and manufactured tools that came from ideas and inventions from locksmiths.

GETTING TO THE JOB SITE

The service van was rare. If you owned an automobile, you carried the tools and equipment in the trunk of your car. Other methods of transportation to the customer consisted of trolley cars, elevated trains and buses. Some locksmiths even took taxis! In Chicago in 1939, there were also a few horse-drawn vehicles.

Some locksmiths used manual key machines which were cranked by hand to duplicate a key. Bit and flat steel keys were duplicated by a file, key machine or hacksaw. A file could be used to re-size the thickness of a steel key in order to fit into the lock’s keyway. Some locksmiths used a basic key machine with a motor directly wired to a vehicle’s 6- volt battery to duplicate customer’s keys. The motor was either a convertible top electric motor, or used a generator and reversed the wiring connection, making it a more powerful motor to drive a key machine. (Today, the alternator has replaced the generator and that procedure cannot be done.)

COMMUNICATION

Two-way radio-equipped vehicles did not exist and there were no cell phones. The telephone served as their initial contact when a customer called. Customer phone numbers were always taken. The serviceman could be contacted at the job, using the customer’s number. When the job was completed, that same phone was used to call the shop to see if there was another service call to be made. Not everyone had phones, but public phones were available for a nickel in most drug stores and major business firms.

LOCK INSTALLATION

In 1939 Chicago, auxiliary locks were mortise dead bolts and rim (surface-mounted) locks of various functions. Auxiliary mortised and rim locks were available in all different shapes and backsets. Cylindrical/tubular deadbolt locks were offered by only two or three manufacturers. About 90 percent of auxiliary deadlocks were rim, with about 9 percent mortise and maybe 1 percent cylindrical/tubular. Some rim locks came with 1” deadbolts, rotary bolts or interlocking deadbolts that would interlock between the lock and the strike plates. Night latches came with just a latch bolt. There were variations that included deadlocking features. Some offered a feature of an extra turn of the key that would enable the bolt to project further into the strike and become a dead bolt. Doors and frames were always made of hardwood, making locks harder to install. Installation tools consisted of a brace and a bit, a hand-driven drill, and if you had one, a Stanley “Yankee” screwdriver.

Many sales people kept their samples and inventory in the trunk. The “jimmy proof” rim lock was the perfect item to secure their products. I remember watching my father and grandfather inside the trunk of cars installing the “jimmy proof” rim locks. Rim cylinder guards were also bolted through the trunk lid to assure the owner further security. That same lock was also applied to sliding doors in trucks of the era.

SURVIVAL DURING THE POST-WAR YEARS

Repair, not replace, was the theme of the period. World War II made new products scarce or unavailable. Locksmiths had to use their ingenuity to survive – and many did! The independent locksmith evolved into a business of its own. Some of the sidelines needed in the earlier years were discarded. It wasn’t until several years after the war that the products we now know as “throw away and replace” first began to appear.

Laurence (Laurie) Simon is a contributing editor who has been in the industry for almost 60 years, just about all of his life. He is a third generation locksmith by trade, with experience in distribution, manufacturing, factory representation and architectural hardware. His web site is www.simon-says.net