The modern safe is a direct descendant of the strongbox. The first safe was patented in England in the mid-1830s and was a lockable heavy metal box. Fireproof safes followed about 50 years later and soon incorporated a combination locking mechanism.

For decades, the only safes in town were the bank vaults. Today, safes are used for many applications and therefore are a vibrant product group for the locksmith. Safes are used to protect the items stored in them and protect individuals from certain items stored in safes.

Most safes sold in the United States have an Underwriters Laboratory (UL) rating or certification for their locking mechanisms, impact resistance, fire resistance and waterproofing qualities. (Gun safes have a separate UL certification system.)

The price of a safe depends on:

- the size

- the design

- the materials used

- the locking mechanism

- the expenses involved in moving and installing it.

Below is a roundup of safes that locksmiths will encounter.

Safes at Home

Once exclusively the province of the wealthy and elite, home safes have become popular in the past 70 years.

Although typically used to protect currency and other small, valuable items from theft, home safes also are used to protect important documents that are difficult to replace, such as deeds, passports, car titles, and marriage and birth certificates.

Around 90 percent of the home safes manufactured today are fireproof, and many models also are waterproof.

Basic home safes come in two varieties: small and large. Small basic safes, also sometimes called microwave safes, essentially are general-purpose locking boxes that weigh 5–25 pounds.

The smallest versions are small enough to fit into cupboards or drawers, hide behind or underneath furniture or pack in luggage. These safes can be moved easily and anchored to walls and floors.

These safes typically are used to deny access to personal weapons, pharmaceuticals and family documents, or to protect the contents from fire or accidental damage.

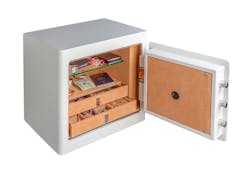

Large basic home safes have anywhere from 0.7 to 2 cubic feet of storage space and provide protection against theft because of their weight, which typically ranges between 80 and 250 pounds. Most on the market today are made of steel.

Along with their increased storage capacity, large home safes often will include built-in or removable shelves, or segmented compartments for easier storage. Some larger models can be bolted to the floor or to walls. Most models are fireproof, and water- and impact-resistant.

A number of specialty home safes are available:

Jewelry safe: Home jewelry safes are basic safes that are designed specifically to hold jewelry. Jewelry safes typically have between 0.8 and 1.25 cubic feet of interior space.

Gun safe: Gun safes are designed to store firearms of various types and ammunition. Some countries require gun owners to store their weapons in gun safes when not in use. In Ireland, for example, anyone applying for a gun license must show proof that they have a gun safe installed in their home before the license will be issued.

Wall safe: Wall safes, also often called hidden or concealed safes, typically are installed by connecting them to the beams and joists inside a wall.

Down to Business

Of course, there are safes designed for business, too, particularly banking.

Vaults: Vaults are basically ultrasecure walk-in safes in which a large amount of valuable material can be stored. They’re found most commonly in the banking industry, businesses that deal in high-value merchandise (jewelers and scientific research facilities) and government agencies.

Smart safes: Smart safes are safes that have a computer incorporated into them. They’re used in bank and other ATMs. Besides storing money, smart safes can perform other functions, such as dispensing cash. Climate-controlled smart safes monitor and adjust temperature, humidity and other environmental factors. One of the largest smart safes is in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Deposit safes: Deposit safes, also called drop safes, have a small door or slot either on the top or in the front of the safe where small items (cash, receipts, etc.) can be put. The items then drop into the body of the safe, and the safe’s door must be unlocked before the items can be retrieved. Deposit safes are used widely in retail businesses that have multiple cashiers and small 24-hour businesses that deal with a lot of cash, such as convenience store.

Safe deposit boxes: Safe deposit boxes are safes within a safe found in banks. Safe-deposit boxes are small personal safes normally installed in a secure room (often the same room as the bank’s vault) that’s monitored 24/7 by dedicated discreet security and video surveillance. Typically, safe-deposit-box locking mechanisms work on a two-key system: a master key used by a bank employee and a customer key.

A Safe Career

My professional experience with safes spans home, commercial, financial, retail and military/governmental.

I took jobs that involved walk-in vaults, bombproof enclaves, high-security applications for the military and Department of Home Security (DHS), as well as residential microwave safes and retail cash drops.

During my career, safe dials transitioned from mechanical to electronic designs, and as with other applications where trusted and time-proven mechanical locks were abandoned and replaced with ostensibly cheap and less reliable electronics, end users and the security industry didn’t greet the changeover with enthusiasm.

Some recollections:

For a period of time, we did a lot of retail banking. This was when banks were heavily into bricks and mortar and having locations that were critical to acquiring clients. Items common to this work were huge vaults with time locks. I recall some exciting situations where the vault clock failed or when the bank would close a location and it required decommissioning a mammoth walk-in vault requiring deconstruction of the building to get the vault out.

Bidding on safe-deposit-box cleaning was an annual event where we had to commit to cleaning all the safe deposit boxes a bank had in all of its branches. Part of the process involved servicing the locks and hardware on these devices. They were typically mechanical key locks using unique keyways and locks.

ATMs in bank vestibules were a big business. Activities included converting electric strike-controlled entry doors that had low-tech entry control to electromagnetic locking systems and card-entry control using the depositors’ bank ID.

There was a period when we were involved in high-security applications, including DHS secure containers, domestic military sites, which were essentially buildings that had exotic locks and safe dials, and NATO crypto installations that were electromagnetically shielded to prevent interception of communications and buried in mountainsides to protect against attack.

Then, there was the more mundane safes work, which included embedding residential safes in concrete.

Installing and removing safes involved the transportation of the safe to the location, then invariably moving up and down stairs. Many times, the safe was too heavy to load into the back of a van, but you didn’t find out until it was too late. Also, even if you had a forklift at your shop, you might not have one for moving a safe on site.

Locksmith Ledger Editor-in-Chief Gale Johnson tells the story of moving a safe in a residence, when the weight of the safe caused the collapse of a stairwell. Moving safes on stairs poses a serious hazard to untrained and under-equipped individuals. Seems as though whenever there was a safe to move, everyone suddenly developed back problems, so they could evade the project.

Cash-drop-slot safes typically were tucked in a manager’s office. For emergencies, we’d have to go to the site and bypass the dial so the manager could get the money. My recollection was we identified the make and model of the safe before going to the job and determining the drill point, where we'd be able to unlock the lock without destroying the vault. Then, we had to make sure we had a suitable dial and latch mechanism, so the vault could be returned to service while we were on site.

Occasionally, the safe would have to be replaced, and the old one had to be pried out of its nest. My strongest recollection was the filth and greasy walls and floors on one particular job. It’s difficult moving a safe on a slippery surface.

Tim O’Leary is an experienced security consultant and a regular contributor to Locksmith Ledger.

About the Author

Tim O'Leary

Tim O'Leary is a security consultant, trainer and technician who has also been writing articles on all areas of locksmithing & physical security for many years.