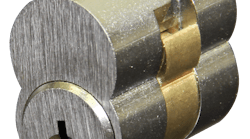

More than 100 million small-format interchangeable cores (SFICs) are in North American commercial use. There also is a significant number of large-format interchangeable cores (LFICs) installed.

This article discusses where the interchangeable core (IC) works best and why it dominates large systems. We’ll discuss what’s inside an IC and why some pin segments work better than others.

Why the IC

As Frank Best explored locking-system challenges 100 years ago, he found two important issues. The first was that existing pinning systems didn’t provide enough codes for larger masterkey systems. Smaller pin segments, however, would allow for considerable code expansion. The second challenge was the difficulty in maintaining internal key control and meeting demands for rekeying.

Although continual change wasn’t much of an issue for smaller customers, larger facilities that had in-house lockshops were desperate for a means to keep up with rapid internal change.

In recent years, key patents became a means of reducing off-site duplication. In larger facilities, keys also are lost, loaned, misplaced, borrowed and stolen. Employees are hired, transferred, promoted and discharged. Buildings and rooms are added, removed and repurposed.

In-house lockshops in these organizations quickly gravitated to the IC as a means to keep up with the constant turnover. Pinning an IC could be done in minutes at the shop and installed in seconds.

Education, healthcare, military, manufacturing, transportation, government agencies and other large-scale users began to adopt the BEST Interchangeable Core. This trend often wasn’t visible to the independent locksmith and still isn’t well understood by many in the industry.

When original patents expired, other lock companies added IC locks to their lineup. Most North American brands now offer SFIC options. Regardless of the door hardware’s housing, all SFICs have a standard form factor, which allows different brands to work interchangeably with each other.

SFIC vs. LFIC

As the IC found its way into construction specs, existing lock companies began to develop LFIC versions, which were compatible with their own keying systems. The size and shape of an LFIC can vary, even if LFICs share the same keyway. In these cases, a locksmith would have to match the door hardware’s LFIC housing to that lock’s brand. LFICs typically use 0.115-inch-diameter pin segments, while SFICs use more-compact 0.108-inch-diameter pins.

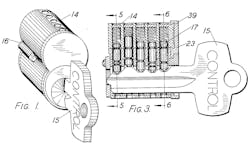

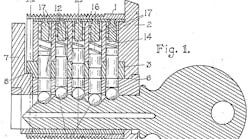

All “figure eight” SFICs use the standard BEST size and shape, and, in the past 50 years, they generally have seven barrels and the popular A2 pinning system. Multiple updates can be made to the A2 system by switching all pins in a barrel from evens to odds, or vice versa. The 16,384 useable codes that include 0.025-inch separation can accommodate multiple revisions.

The A4 system provides five codes in each barrel and 0.021-inch separation between cuts. This provides 78,125 useable codes per keyway. The even-odd switching isn’t possible in the A4 system. (Missing A1 and A3 systems aren’t produced, because the spacing between the key cut is too small to provide adequate security.)

SFICs generally have individual caps to allow for easy repinning of a single barrel when a key is obsolete. LFICs, however, generally use a slide cap that exposes all barrels and have a larger diameter lower section. The larger pin segments, of course, are easier to handle. LFIC locking lugs are in various locations and are controlled by two or three of the barrels, whereas the standardized SFIC locking lug is controlled by all six or seven barrels.

LFICs allow a lockshop to continue an existing system across various cylinder or core types. A second benefit of the LFIC is that additional devices, such as sidebars, can be included easily. These additional components allow for exponential increases in system size, but the trade-off can be complexity, cost and labor content.

Electronics

In the early days of electronic access control (EAC), some presumed that internal key control or management no longer was necessary. This assumption was proven incorrect, because most losses actually resulted from internal compromises. It soon became clear that to be effective, mechanical and electronic systems must be coordinated.

The same three things are necessary for internal control of mechanical and electronic access:

- Policy

- Key or credential holder agreement

- A record of doors, keys (or credentials) and key holders.

In the recent past, some interesting electronic cores emerged in the LFIC space. CyberLock and Medeco’s XT products incorporated the companies’ smart keys and cylinders into a variety of LFICs. (CyberLock also builds an SFIC version.) ASSA ABLOY’s hybrid CLIQ LFIC product allows the electronic key to operate in mechanical locks as well.

BEST introduced the Switch Core, which fits into existing SFIC housings. The Bluetooth-operated core is part of dormakaba’s emerging suite of Switch Tech EAC systems and uses mobile credentials.

What’s Inside

Each manufacturer seeks to maximize its technical and market strengths, and that drives the different design approaches. For example, SFIC manufacturers tend to emphasize simplicity, recovery speed and low labor content.

Corbin Russwin, SARGENT, Schlage and Yale long have focused on keying continuity for existing customers. Medeco has stressed high levels of pick and tamper resistance. Here’s a rundown:

- BEST builds only the SFIC, although it now provides housings to accommodate most conventional and LFIC systems. The company has focused on keeping system maintenance practical and cost-effective. Typical manual pinning takes 6 minutes per core, including capping and testing. More-nimble fingers do this in only 4 minutes. Although key audits have proved effective in preventing external duplication, the company also provides a thick premium key, as well as the patented Kaba Peaks and BEST’s CORMAX series, which has a slide pin at the rear of the core. BEST SFIC cores also are available with UL437 ratings.

- CX5 has been able to maintain the same sidebar and finger pins in its LFICs and SFICs. The “Wave” side slot aligns the finger pins with 60 different configurations for each keyway in the patented system. UL437-rated cores are available in the LFIC version.

- Corbin Russwin’s LFICs allow for installation of its Pyramid high-security keying system, which includes side pins, a bottom blocking plate and seven barrels. This allows for expansion of existing keying systems.

- Medeco builds a wide variety of ICs for nearly every type of application. Medeco’s SFIC is available in standard configurations and the X4 version, which adds an auxiliary locking pin at the bottom entrance of the keyway. The company long has promoted patented keying as a means to prevent off-site duplication. The new Medeco 4 key system adds a shuttle pin held near the nose of the key. A ramp inside the core forces the shuttle to activate one of the sidebar pins. This tweak is expected to extend key patents for several years. The M4 system is available in Medeco and Yale LFIC designs, while only the Medeco version is UL437 listed. Corbin Russwin, SARGENT and Schlage LFIC versions are under development.

- SARGENT’s LFIC products use the Degree system, which has three security levels. DG1 includes a patented key and sidebar. DG2 adds a slider and chisel-point bottom pins. DG3 adds hardened inserts to defend against drill attacks for its UL437 listing.

- Schlage now includes the narrower A2 pin segments in LFICs and SFICs, as well as conventional cylinders. This allows the full seven-barrel configuration for larger systems with Schlage’s Everest 29 SL version of the patented keying system. L-pins control the sidebar, while a bottom check pin adds another layer.

- Yale KeyMark uses an angled Security Leg to provide multiple keyway profiles while adding tamper resistance. The LFIC format allows integration with existing Yale keying systems. SFICs use the standard A2 or A4 pinning systems and can be obtained to service many older BEST keyways or Yale KeyMark profiles.

IC Pins

Pin segment material and design play an important role for IC operation. This is even more important in close-tolerance BEST SFIC cores. Machining accuracy, material, coatings, chamfer, radii and lubrication all play important roles in smooth operation. So, what really matters?

When Best began to develop the IC in the 1920s, he found it difficult to maintain desired accuracy by using existing equipment. Robert Labbe found the same challenge when he began to make pin segments in 1956. Both entrepreneurs refined their equipment beyond existing standards to advance the state of the manufacturing art. LAB shared with us some important details about why some 0.108-inch SFIC pin segments work better than others.

- LAB’s BEST OEM Spec nickel silver pins are engineered specifically for BEST cores. These bottom pin segments have a specific top chamfer and flat-bottom nose to match the precision-punched nickel silver BEST key blank.

- LAB Original nickel silver bottom pins have a rounded nose to work with nickel silver keys cut on conventional machines. These are used on all SFICs except BEST.

- LAB Universal SFIC color-coded segments come with standard 0.108-inch diameter hardened brass bottom pins. These pins also have a rounded nose designed for use with brass keys in non-BEST cores.

BEST cores are reported to work considerably better with original BEST brand pin segments or with the LAB BEST OEM (not color coded) pin segments noted above. Some locksmiths choose to put up with the less reliable operation for the convenience of the colored pins. Check page 24 of the LAB catalog for details.

ICs allow locksmiths to keep up with the constant change found in larger facilities. They also are popular with chain stores, real-estate managers, apartments and other operations that tend to have multiple sites or more internal turnover.

LFICs allow facilities to continue existing keying systems and include additional mechanical or electronic devices.

Finally, it appears that electronic miniaturization is giving the IC a new lifecycle. Like the proverbial cat, the IC has several lives remaining.

Cameron Sharpe, CPP, worked 30 years in the commercial lock and electronic access industry. [email protected]