How to Sell and Install Access Control

The access control market is a high-growth business where sales revenues for 2016 were in excess of $6.39 billion. By 2023, industry experts expect this number to reach $10.03 billion with a Compound Annual Growth Rate of 6.48 percent.

According to the new market research report cited above, the major driver for this growth is the high adoption of access control solutions, largely owing to growing security concerns on a global basis. The overall access control market is driven by factors such as technological advancements and deployment of wireless technology in security systems, and the adoption of ACaaS (Access Control as a Service) and mobile access control is a significant part of this growth pattern. (http://bit.ly/2HEr17r)

“What that means to you and I is an opportunity to expand our locksmith businesses by providing turnkey access systems -- not just the equipment and labor for the door work, but the entire system,” says Steve Norch, president with Bierly-Litman Lock & Door of Canton, Ohio. “Of course, there’s great money to make installing door hardware for access, but why settle for only a slice of the pie when you can have it all?”

There are two basic kinds of access control systems on the market today--wired and wireless. Norch’s company is technically capable of doing both.

“I realized some time ago that unless we expanded our operations into EAC (Electronic Access Control), we’d eventually paint ourselves into a corner without any wiggle room,” says Norch. “Of course, there are advantages to doing both wired and wireless.”

In this Locksmith Ledger article, we’ll take a look at the rudiments associated with both.

Take Inventory and Plan Accordingly

Selling an access control system usually begins with a phone call from a prospective client who’s interested in more than just an ordinary mechanical lock on a door(s). The best course of action is to begin by listening to what the prospect has to say. Find out what he/she wants or needs. Take notes, make drawings, and take pictures so you can recall every detail when you’re back at the office working on the proposal.

“I spend a lot of time discussing what my prospects want to accomplish. This gives me a lot of information to work with. First, it gives me a basic idea of which system(s) will accomplish the client’s goals. It also gives me an idea of what the budget is going to be. This also is a good time to give them a conservative price per door so they know ahead of time what is involved,” says Norch. “If we’re on the same page I’ll go ahead and set up an appointment to do a walk through. I always do a walk through to give an estimate. I then can make suggestions on where they might be able to save money. Most commonly I suggest they make employees enter and exit through a single door. This ensures the facility is locked down and limits the doors that require access control.”

Whether it’s wireless or wired, the process begins with a basic inventory of the facility. Find out how many doors (not every door needs to be included), the exact location of each one, and what kind of credential/authentication hardware the client wants. Common choices include keypads, proximity, iClass card readers, RFID (Radio Frequency Identification)-chipped cards/fobs, and biometrics.

Also of great importance is the type of locking hardware presently in use. Be sure to evaluate the type of locking hardware and the type of door(s) on which it is mounted. If possible, use networkable wireless keypad/readers or electronic locks to start out with. The latter enables you not to worry about a boat load of fire codes, as is the case when working with cable as well as electromagnetic locks (see ‘How To Install Electromagnetic Locks For Life Safety,’ http://bit.ly/2HbdkQt).

Another necessary commodity is electrical power at each access-controlled door. If receptacles are not available at or near each door -- above or below ceiling level -- call a licensed electrician for a quote and offer it in your proposal as an option. Whatever you do, don’t install these receptacles yourself, unless you have an electrical license to do so. This is especially important when a permit is required for the job because there’s always an intense inspection later. This s should be an option so the client is free to contract this part of the job out to their own electrician.

During the course of your work with the client, see if you can obtain an accurate blueprint of the facility to work from as you’ll probably need it in order to get a permit for the work. Add the cost of new blueprints with your access control system placed on it with a one-line drawing with the specifications of your new system on it. These blueprints will have to be stamped by a certified architect or a PE (Professional Engineer), so be sure you do your homework and add these additional costs to your price. Or, better yet, add a clause that states “All fees associated with plans approval and permit fees to be paid for by the owner” (we’ll cover the permit process from A to Z in a future article).

It’s also important to find the prospect’s expected budget, as mentioned earlier by Norch.

Access Control System Architecture

Access control systems come in many shapes, sizes, and flavors -- such as wireless versus hardwired or keypad versus card reader. There are many kinds of credentials on the market as well to choose from, such as those mentioned in the previous section. Wired systems are pretty simple when you take the time to study them and wireless ones are even simpler to install.

For example, according to Norch, “Most of the readers [and keypads] now can be run with Category 6 cable which is made up of 4-pair, 22 gauge conductors. It’s good for most card readers and keypads that we install and it can be used for network cable as well. I use 18-2 to power the hardware if needed. As for the connectors, at the readers I use are Ideal-made weatherproof connectors.”

Most of the card readers out there operate using a five- to eight-conductor cable. Most manufacturers call for an 18 gauge cable, but you can, on relatively short wire runs, get away with Category 5e or 6 cable, as stated earlier by Bierly-Litman’s Norch. Because the EDC (Electronic Door Controller) and keypad/readers are usually relatively close, this will usually work for these as well. Connections at the keypads/readers is usually are made up of flying leads, which means you have to strip out the cables and connect them to the incoming network cable (see photo on page XX).

Five of the conductors in this cable are needed for data transfer from the keypad/reader to the EDC and consequently to the host. This is because most of them use what is called a ‘Wiegand data transfer format.’ The additional conductors are for additional features at the keypad/reader, such as a green LED (Light Emitting Diode), red LED, and a small piezo-alert sounder that will sound an alert under certain programed circumstances.

As an aside, be sure that the Wiegand data format matches the readers and EDC/host. Where some use a 26-bit format, others use a 36-bit format. This is all you really need to concern yourself with as it pertains to Wiegand. If the two or three do not match, the client will not be able to provide automated access through doors in his/her facility.

When in doubt as to how many conductors to use as well as the gauge of the wire simply is, “Follow the manufacturer’s installation instructions.”

Nuts and Bolts of Networked Access Control

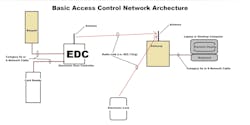

Keypads and/or card readers communicate with a centralized access control computer, also referred to as a ‘host computer,’ using cable that connects to an EDC. Both essentially provide a unique numeric code that identifies the individual requesting access.

Traditionally this data travels from the keypad/readers to the host, either by wireless or through cables via an EDC. In the latter case, Category 6 cable links each EDC to the main host while the former uses ordinary 802.11b/g (WiFi). Others may use a proprietary, encrypted RF (Radio Frequency) technology.

No matter which one it may be, most of these wireless access control systems on the market today use one or more remote access points within a single or group of buildings equipped with a common LAN (Local Area Network). These access points, usually referred to as “gateways,” act as a data transfer point between the keypad/readers in the systems and one or more EDC’s--each one located at or near each door or pair of doors. A single Gateway will typically control up to 63 doors using a single host, which usually is a non-dedicated, Windows-based PC (Personal Computer).

EDC’s are also designed to monitor each door under its control for intrusions and hold opens--also called “door ajar.” The EDC also contains the necessary relays for door lock control including manual egress--all according to NFPA (National Fire Protection Association) fire code standards (NFPA 72, 101, 70, and others).

Wireless extenders also act as bi-directional repeaters, extending two-way data communication between electronic locks/EDC’s and one or more gateways. Extenders can be installed throughout a facility, making it possible to stretch the natural range of a single gateway or to add to an access control system at any time after the initial installation.

No Such Things as “Wireless Only”

Truth be known, no wireless access control system is truly entirely “wireless.” No matter what we do, no matter what we install, there’s a certain amount of wiring that must be used in order to make all the keypad/reader EDSs work.

In most systems, wiring is installed to one or more wireless gateways either individually using a network switch (managed or unmanaged) or in daisy-chain fashion where a single wire is installed between each one (see the ‘Access System Architecture’ drawing on page XX). Most of these network oriented systems are considered as plug-and-play.

The data connections in many gateways is provided by a set of screw terminals so all you have to do is strip the insulation off the end of the wires, insert each one into its designated screw terminal, and tighten them with an appropriate screwdriver. In some cases it’s performed by plugging an RJ45 modular jack into a corresponding Category 6-compliant female plug installed at each gateway or extender location.

Network oriented systems use network cabling and RJ45 plug-ins while older EIA 485-oriented access control systems use screw terminals. Both methods of connection are commonly used today by professional access control installation companies.

Access Control System Programming

Once the new system is installed, it’s time to power up and set up the system in programming. This usually is performed using a special software loaded into one of the client’s Window-based PC. In some systems there is no software to load. Instead the necessary software takes the form of firmware pre-loaded into a central controller, thus allowing the client to use a common, ordinary browser of his/her choice to do the necessary programming.

In Norch’s Alarm Lock Networx installations, a free software package effectively controls all the keypad/readers, EDC’s and electric locking devices. When installed on a single, non-dedicated PC, it determines how the system will react with each authorized user. Once the program is loaded into each of the EDC’s in the system, the host PC can be taken offline and used for other things in the client’s office.

The programming loaded into the EDC(s) effectively enables electronic locks or standalone keypad/readers in a system to communicate using a single, common database, which means that each user’s information need only be inputted into the system once, thus sharing a single database with an entire company full of people across many departments, such as security, accounting, and HR (Human Resources).

New employees are issued a new card or keypad PIN (Personal Information Number) and when HR is finished entering all the necessary data for a new hire, all of this information becomes available to every other department in the company. For example, when security creates an ID badge/card, the same photo is shared with HR and others in the company for a variety of purposes.

Programming is fairly straightforward and simple in that today’s systems software are designed to “go out and find” every device in the system, assign each one an IP (Internet Protocol) address and enter them into the database according to function with labels specified by the client. This includes each reader, keypad, door lock, and other devices--all in accordance with the client’s unique nomenclature.

The client will have to be trained on how to enter and remove users as needed, take photos and use them for badges/credentials, as well as determine and enter functionality presets for groups and individuals based on access controlled doors, time of day, day of week, holidays, and other criteria. It’s not unusual for a small to medium-size access control system to accommodate 5,000 to 10,000 users or more.

Besides user training, it’s also your job--or that of the client’s IT department--to deal with connectivity issues to ensure that each keypad, card reader, EDC, and any other control device is able to “talk” together as a network. Thus, unless you have an IT-savvy tech on staff, it might be a good idea to partner up with a local IT company or a network tech-savvy individual in your community who can work with you whenever the need arises.

There’s no doubt that jumping into EAC systems is a serious move for a mechanical locksmith. But careful planning and study, along with the right decisions on your part, will make the process work so you’re successful in the end analysis.